"This new cold war will be far worse than the first"

/prod01/twu-cdn-pxl/media/images/history-government/jamison2024-missile-900X600.jpg)

Cold War historian Mary Elise Sarotte to speak at Jamison

April 3, 2011 – DENTON – When Mary Elise Sarotte speaks at this year's Jamison Lecture on April 11, you should listen.

Not because Sarotte wrote the award-winning book on events that have led to a new cold war and a hot war in Ukraine, Not One Inch: America, Russia, and the Making of Post-Cold War Stalemate. Not because of her impressive academic credentials, or because she has lived in Berlin and visited Moscow.

Listen because Sarotte's area of expertise is, now more than ever, vitally important to understanding the world. And because she knows of what she speaks.

For example: in early 2021, with the approach of the 30th anniversary of the December 1991 end of the Cold War, collapse of the Soviet Union and Ukrainian independence, Sarotte was watching for some sort of commemoration by Russian president Vladimir Putin.

"He has a long history of doing violent things on anniversaries," Sarotte said. "He kills dissidents on his birthday and things like that. There's a clear pattern.

"I had no idea what Putin was going to do," she added. "I wasn't psychic in that regard. I just knew something was going to happen."

Then in the spring of 2021, Russia began massing troops on the Ukrainian border, and Sarotte knew not only what Putin would do, but when.

"In 2008, Putin stole the headlines from the Chinese 2008 Olympics by invading Georgia," Sarotte said. "The Chinese said to him, 'Do not mess with another one of our Olympics. We're going to have the Olympics in early 2022, and we don't want you to invade a country before it.' And then I thought, oh, my God, he's going to do it right after the Olympics. Thirty years after this divorce between Ukraine and Russia, Putin is acting like a bitter ex who still doesn't accept that the split happened, and is going to use force to take back what he thinks is his.

"What was challenging was convincing other people. I tried to place an op-ed with the title, 'Deadly Anniversary of a Divorce.' I circulated it to the New York Times, the Washington Post, pretty much every meaningful English-speaking publication. They all turned it down."

People told her Putin was trying to scare the Ukrainians. Saber rattling. Just an exercise.

"I'm like, no, this is not an exercise," Sarotte said. "This is real."

China's Winter Olympics began Feb. 4, 2022, and concluded on Feb. 20. Four days later, as Sarotte feared, Russian infantry, armor and aircraft attacked Ukraine.

"Those media outlets that had said no to my op-ed all emailed me, called me, said, 'Did we say no? That was a misunderstanding. We meant, yes. Can you write this right now?'"

Sarotte quickly wrote an essay, "I’m a Cold War Historian. We’re in a Frightening New Era.," which ran in the New York Times on March 1. It included a chilling warning: "…I fear that Russia’s invasion, regardless of its outcome, portends a new era of immense hostility with Moscow — and that this new cold war will be far worse than the first."

So, yeah, when Sarotte speaks, you should listen.

"I'm doing my best to try to say to people, we need to really understand the history because it's what's motivating," she said.

2024 Jamison Lecture

Guest speaker Mary Elise Sarotte

Thursday, April 11, 2024, 7 p.m.

Phyllis J. Bridges Auditorium in the Student Union at Hubbard Hall

Open to the public and admission is free

Sarotte's journey to becoming an expert on the Cold War and its aftermath began at ground zero of the events that culminated in the collapse of the Soviet Union: Berlin. She had earned a bachelor's degree from Harvard and was studying abroad in West Berlin in 1989 – the year the Berlin Wall came down.

"That was a life-changing experience," she said. "I decided to become a historian. Fast forward, I go to grad school (at Yale) to get a PhD, and I write books about the Wall coming down and about German unification. As I'm doing this, I'm stumbling across documents about NATO enlargement, which people are telling me don't exist because they're saying it has nothing to do with German unification. It never came up, et cetera, et cetera.

"And I'm like, okay, but I got all this stuff here. So at the beginning of this century, as I'm writing the other books, kind of in the back of my mind, I thought, you know, I'm going to start collecting stuff on NATO enlargement. And one day, if I get enough, I'll write a book. I started in a really targeted way in 2005. But I thought, I'm not going to try to get a book contract or anything because there's so much out there that's written on speculation, and I don't want to write on speculation. I want to write on evidence. So I'm only going to write the book when I have enough evidence."

She kept digging, doing interviews, reviewing documents and filing Freedom of Information Act requests, which required a high degree of patience and persistence.

"They take years," she said. "But then I would get some back, and there would be stuff in it. So I'd file follow-up requests, and I just kept doing this in parallel to everything else I was doing from 2005 until about 2017.

In 2018 came a major breakthrough: an appeal for declassification to the William J. Clinton Presidential Library was granted, releasing material involving President Clinton and former Russian President Boris Yeltsin.

"Took me three years, but I got all the transcripts of the Clinton-Yeltsin summits, the briefing books beforehand, the after action reports afterwards," Sarotte said. "Then I started to realize, I think I have enough stuff. I actually have enough evidence."

But as the 30th anniversary of the Cold War's end loomed, Sarotte was hard pressed to find the time to go through the reams of research and write the book. And it had to be published before the end of 2021.

That meant finishing her work up to a year before the publishing date to allow for editing, rewriting, polishing, cover design, advance reader copies, editorial reviews, printing, marketing and distribution.

"So at the beginning of 2020, I knew that the manuscript basically had to be done by the end of 2020," Sarotte said. "I thought the only way I'm going to be able to do this is by canceling everything I have to do in 2020 and stay home all year."

Enter the COVID pandemic.

"Suddenly, everything in my calendar canceled in 2020," Sarotte said. "I stayed home while I wrote a book."

What emerged is a tome lauded from both sides of the Atlantic, from academic and editorial reviews. And it has dramatically changed Sarotte's life.

"My life has been really different since the invasion," she said. "Just so many invitations to, so many briefings. Last month, I spent two and a half hours with the secretary general (of the United Nations, António Guterres) and two aides because he said, 'it's clear to me that Putin is obsessed with his history, and it's also clear to me that you know it. So I'd really like to just talk through it with you so I understand the history of these events for myself.' I said, sir, it's an honor to help you ask as many questions you want. I'll do my best. I'm really gratified that now people see the importance of this story, but it's just so tragic that took this kind of event."

The book's title is well chosen on multiple fronts, from American secretary of state James Baker's 1990 offer that if the Soviets relinquished control of East Germany, NATO would "not shift one inch eastward from its present position;" to, as Sarotte wrote, "not one inch of territory need be off limits to NATO" in the face of the collapsing Soviet Union; to Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy's refusal to cede one inch of Ukraine to the Russian invaders who have laid waste to its cities, butchered its men and women and kidnapped its children.

* * *

The Russians know Mary Elise Sarotte.

If they didn't know her from her three previous books (The Collapse: The Accidental Opening of the Berlin Wall; Dealing with the Devil: East Germany, Détente, and Ostpolitik; and 1989: The Struggle to Create Post-Cold War Europe), she got their attention doing the research for Not One Inch.

Amid her freedom of information act requests and declassification requests, one drew the ire of the Kremlin. Dmitry Peskov, press secretary for Putin, issued a complaint in 2018 when the Clinton Presidential Library released its documents. The complaint was publicized by the Russian news agency TASS, to whom Peskov bemoaned the lack of coordination or consultation prior to the transcript's release.

Which was a nice ― if unintentional ― way for the Russians to tell Sarotte she was on the right track.

But then the Russian objection took an ominous turn.

"I got an email out of the blue about 2 November 2021, three and a half months before the war started, from a political scientist who was known to be affiliated with the Kremlin asking if I wanted to come to Moscow."

This is the same Moscow that arrests and imprisons American journalists, businessmen and basketball players, much less a historian poking her nose where the Russians felt it didn't belong.

"My answer was a hard ‘no,’" Sarotte said. "I've heard now from a variety of diplomats that Russians will show up to meetings with historical documents, including some I've gotten declassified, and they'll say, 'Well, because of this, we're justified in doing whatever.' Makes my husband a little nervous. Yeah, that would have been a bad trip to Moscow. I would not have come home.

"Too bad," she said. "I like Moscow. My assumption is I'm never going to Russia again, which is a shame. Everyone I knew in Russia has now fled. It's a little surreal when I go to Berlin, which I do a lot because I used to live there. Pretty much everyone I knew in Moscow is now in Berlin."

* * *

If you're still having a difficult time getting worked up over another Cold War and its associated hot war in Ukraine, consider how close the first Cold War came. To appreciate just how close, drive north up Locust Street, about four miles from the TWU campus.

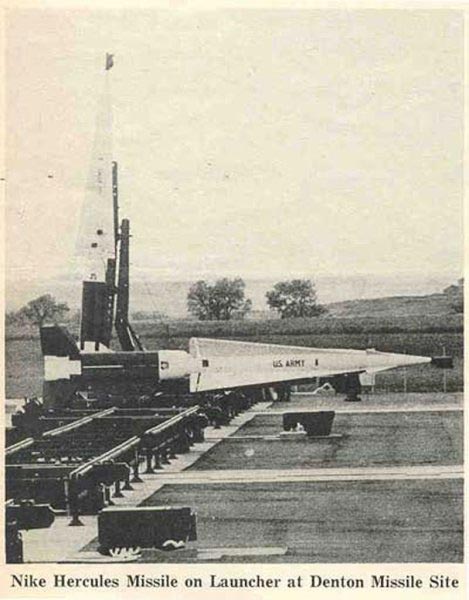

There's very little to mark the spot today, just a gravel road, a cattle guard and a fence with a “NO TRESPASSING” sign in an overgrown area on the west side of the street. A thousand feet behind that fence is a crumbling concrete pad more than 500 feet long and 200 feet wide, studded with rusting metal hatches. It's marked on maps as "DF-01 Nike missile site." Active 1960-68, it was home to Battery A, 4th Missile Battalion, 562nd Artillery of the Army Air Defense Command, 4th Region. It was a United States Army base with underground bunkers containing a Nike Ajax missile and two Nike-Hercules long-range, high-altitude anti-aircraft missiles.

There were more than 200 such bases. This one, along with bases in Terrell, Mineral Wells and Alvarado, protected the Dallas-Fort Worth area. In minutes, base personnel could raise the missiles into position and launch.

The Ajax carried a conventional warhead.

The Hercules were armed with nuclear warheads.

That's right. There were nuclear weapons just four miles from the TWU campus.

If relations between the United States and Russia had gone sufficiently south – which they very nearly did on multiple occasions – the base could have been targeted by a Soviet bomber or intercontinental ballistic missile. DF-01's missiles might have shot down a bomber, but not an ICBM.

Once launched, an ICBM's warhead would reach Denton in about 26 minutes. By the time the warhead was in range of DF-01's Nike missiles, it had long since been deployed by its ICBM launch vehicle and would be in its terminal phase, descending at 15,000 miles per hour toward its target. Against a warhead, the Nikes were useless. Even today, there is precious little American forces can do to intercept a warhead. In the 1960s, there was nothing.

The thermonuclear warhead's detonation would have generated a superheated flash hotter than the sun, consuming the base and nearby houses and farms and instantly killing base personnel and surrounding civilians. The expanding fireball and shockwave, moving at hundreds of miles per hour, would have destroyed TWU and much of Denton. Devastation and fire and radiation for miles. Thousands annihilated. Thousands more dying in the hours and days to come.

And Denton residents knew it. What we called the North Missile Base was no secret. Its groundbreaking ceremony was publicized in the local paper. Cold War generations around the world grew up with the very real threat of their lives ending beneath a mushroom cloud, a dread amplified by films like On the Beach, The Day After and Threads, but living in proximity to even a tiny portion of the arsenal of mutual assured destruction made the Cold War feel much hotter.

The troops, missiles and associated equipment are long gone, and the University of North Texas has used the site as storage and the location for KNTU's radio tower. But that derelict relic of the Cold War is impossible to forget.

Especially now that a new Cold War is heating up.

"Thirty years after the end of the Cold War, they (the U.S. and Russia) still have 90% of the nuclear arsenals," Sarotte said. "Therefore, there is nothing more important than the relationship between the two and whether or not they're about to use those arsenals against each other, period. And that's why I do what I do."

2024 Jamison Lecture

Thursday, April 11, 2024, 7 p.m.

Phyllis J. Bridges Auditorium in the Student Union at Hubbard Hall

This year's speaker is Mary Elise Sarotte, a leading expert on foreign policy and the Marie-Josée and Henry R. Kravis Distinguished Professor of Historical Studies at the Henry A. Kissinger Center for Global Affairs at Johns Hopkins University.

The first 50 students to attend the lecture will receive a free, signed copy of Sarotte's book, Not One Inch: America, Russia, and the Making of Post-Cold War Stalemate. The lecture is free and open to the public.

Media Contact

David Pyke

Digital Content Manager

940-898-3668

dpyke@twu.edu

Page last updated 5:12 PM, April 12, 2024

/prod01/twu-cdn-pxl/media/images/history-government/northmissilebase1964-900X600.jpg)

/prod01/twu-cdn-pxl/media/images/history-government/northmissilebasetoday-900X600.jpg)

/prod01/twu-cdn-pxl/media/images/history-government/jamison2024-launchpads.jpg)